Do the Crusades show that Christians shouldn't be trusted to make decisions in ethical matters?

Hear the sermon by clicking the link to the right--->>>>>

This is the third week of our sermon series on “big

questions”. We asked you what your big questions are about God, the church, or

the Bible. The question today is a bit complicated. I was in a coffee shop that

is a bit like my 3rd office, and I asked the barista there what her

big question was, and she said something like this,

“I think about the crusades and the horrible things Christians did back then, and I think about how trans-gendered people and gay people have been treated. I also think about Christians not being allowed to marry non-Christians, or divorced people. Even if they are tolerated, they aren’t really accepted, they are sort of cut off from Christianity. There seems to be such a difference between modern ethical values and Christian ethical values. How do you use an ancient book like the Bible and use it to help you have ethics that are relevant for today”.

It is a complicated but important question. Sometimes

Christians have done things that seem horrible. There are all kinds of

examples- the crusades, the witch trials under the Inquisition. A modern

example might be the residential schools. There is no shortage of examples of

horrible things Christians have done or have been involved in. With that kind

of a track record how do we think that we can have any real ability as

Christians under the direction of the Bible to make good ethical decisions

today especially regarding issues like marriage and sexuality? Some in our

culture are suspicious of the Christian ability to make ethical decisions based

on some of these past events.

I think we have to deal with this in two parts. First, we need to look a historical

incident that is used to attack the Christian ability to have relevant ethics

for our modern world. And second, we

need to look at how Christians should make ethical decisions.

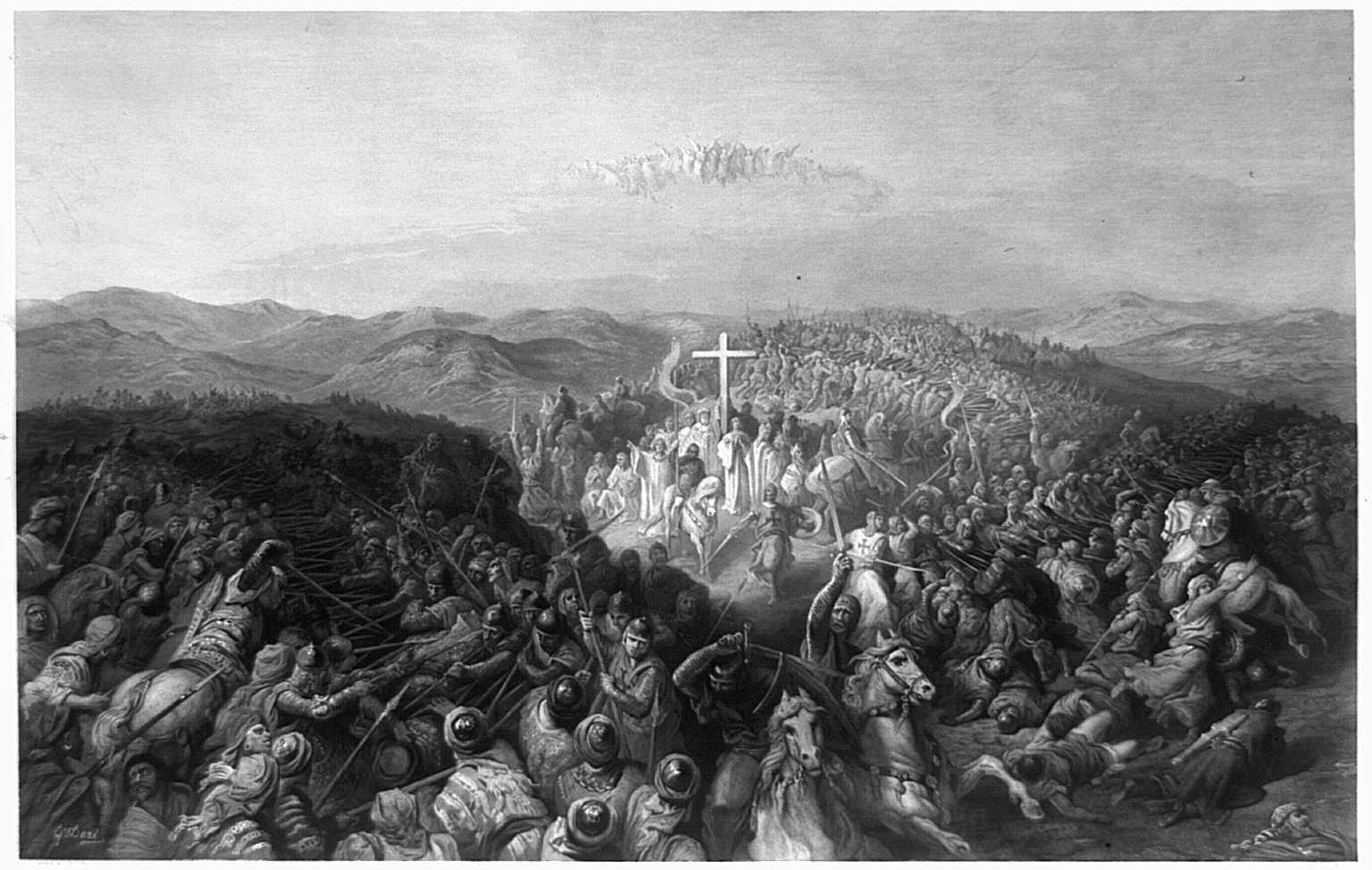

So first, we will look at the example of The Crusades as a

historical example that is often used to show Christians behaving badly, which

is also often used to discredit Christian ethics. “The Crusades” has become

short-hand for all that we hate about Christianity of the past. We see it as

white Europeans violently attempting to oppress and control other parts of the

world. We envision savage and bloodthirsty European soldiers seeking to steal

land and valuables and justifying it all through Christianity. We imagine

power-crazed church leaders exhibiting their authority at the end of a sword,

and knights destroying peaceful and enlightened people. The Crusades have been

referred to numerous times in the attempt to understand the turmoil in the

Middle East, especially since 9/11.

But, The Crusades are much more complicated than that

caricature allows. We can’t really get into too much detail, but I would like

to give a bit of context that might help us to understand the Crusades a bit

better. The first crusade was called in 1095 by the pope (Urban II) and the

Crusader forces arrived in Jerusalem in 1099.

We can’t really understand the Crusades without understanding

something about the rise of Islam. Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, died in 632.

Within ten years (by 642) Muslim armies invaded and conquered the countries we

know as Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Armenia, Iraq, and Iran. Soon, the Muslim

armies expanded their territories stretching across North Africa, to

Afghanistan and India to the West, Yemen to the south, the area between the

Caspian and Black Sea, Portugal, and Spain. By the early 700’s these armies

were pushing into France. They took over most of Turkey and were threatening

the city of Constantinople. These armies continued to expand taking the islands

just off Spain and the island of Sicily. They even pushed into parts of Italy.

In a very short amount of time Islam overtook over half of what had been

Christian territories. In early Christianity there were considered to be 5

major centers of Christianity in the world. After the Muslim expansion only one

of those centers remained outside Muslim control, which was Rome.

It is hard to Imagine ourselves into the situation that led

to the crusades, but imagine China invades North America then takes over the

United States, the Maritimes, Quebec, and on the other side they take over

B.C..

The 1st crusade was called because the Byzantine

Emperor (Alexios l Comnenus) asked the pope for help in the 11th

century. He was witnessing his lands being attacked by Muslim Turks. In

addition to this plea for help there were also many reports about pilgrims

traveling to the Holy Land, as well as Eastern Christians (who had been living

in these lands since the time of Christ) being robbed, enslaved, and killed. Furthermore,

there were other reports from earlier in the century. For example, In 1009 the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which is very likely built over the empty tomb,

was destroyed along with 1000’s of other churches in the holy land. These were the

holiest sites for Christians. For example, Jerusalem was so important in the

medieval mind that in medieval maps of the world Jerusalem was placed at the

very center. It was the place where Christ died and very near the place where

he was born.

If you’ve been at St. Timothy’s during Remembrance Sunday

you’ll know that I have a very hard time seeing war as something Christians can

participate in. So, I’m in no way defending the Crusades as acts of war. I do,

however, think the Crusades are a relatively rational reply for those who are not

pacifists as a response to invading military forces and a plea for help from the

emperor of those territories. Now some

Crusaders did horrifying and awful things. Some armies were rag tag groups that

responded to the pope’s call by first attacking many local Jewish communities.

They even attacked local bishops that tried to stop them. Also when a crusader

force took Jerusalem there was a massive slaughter of Muslims, Jews, and even

many local Christians. So there were horrifying and evil things that took

place, and to begin grasping these actions we would have to look into medieval

warfare and the conditions the armies experienced. … But, in general, the

Crusades were a defensive action. There was no attempt to recover any of the

other areas taken by Muslim armies. The main target was the Holy Land. With

that context I hope that we can see that the Crusades are not the simple

caricature we are sometimes presented with. This isn’t to say that that churches

or Christians are innocent of crimes in the past. All I’m trying to say is that the historical

reality of the Crusades are more complicated than the stereotype that is

sometimes thrown in our faces.

We don’t have time to go into all the cases that are often

used as examples of Christians behaving badly[1],

but I just want us to know that usually these are stereotypes and when we look

into the history we often find a mixture of forces both cultural and religious-

both virtuous and sinful- at work in these histories. They existed within a

different worldview and quite often were doing the best they could given their

context. This isn’t to say horrible things didn’t happen, it’s just to say these

historical cases are more complicated than they are usually presented and definitely

shouldn’t be used as example of why Christians can’t be trusted to make ethical

decisions.

This brings us to the

second part of our question. We will

now turn to how Christians can make ethical decisions under the direction of

the Bible. In some ways this overlaps with what Regula said last week about seeking

the will of God. What I’m going to be

speaking about is the more general directions from God about what is right and

wrong, rather than who to marry or whether you should get married or not. I’m

not going to get into the specifics of sexual ethics or marriage (that topic

needs at least a sermon on its own).

If we randomly flipped open our Bibles and blindly put our

fingers on a verse, we might land on Leviticus 19:19-

“you shall not sow your field with two kinds of seed; nor shall you put on a garment made of two different materials.”

If we then opened our Bibles randomly again we might land on the

verse, Exodus 20:13-

“You shall not murder”.

If we do it again we might land on

Matthew 5:44-

“Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you”.

And if

you did it again you might land on Levitucus 20:9-

“All who curse father or mother shall be put to death”.

All these are in the Bible. Shouldn’t we be

applying all these directions to our lives?

But then we read in Paul’s letter

to the Galatians that, “if you are led by the Spirit, you are not subject to

the law” (Gal 5:18). So we are in some way free from the law. …

The Bible

is not primarily a law code full of commands to obey. Primarily, it is a story

that we are invited into.

The New Testament scholar and Bishop N.T. Wright has a

helpful way of imagining how to apply the Bible to our lives. He imagines that a lost play has been

discovered. It is a Shakespeare play that no one knew about. It is a 5 act

play, but they only recovered the first 4 acts. A famous director is asked to

perform the play, but they aren’t sure what to do with the missing 5th

act. So he hires very experienced Shakespearean actors who know the rest of

Shakespeare’s plays inside and out. They practice the first 4 acts over and

over and on opening night they improvise the missing last act. As they

improvise the last act they can’t simply go back and repeat a previous act.

That would be strange and it wouldn’t forward the story at all. But, they also

couldn’t just do something completely different and act out an episode of Dr.

Who. There has to be continuity with what has taken pace in the previous 4

acts. As they improvise the last act they have to allow it to flow from the

other 4, but it also has to progress and have its own integrity as an act in

the play.

As Christians we are living the 5th act right now.

It wouldn’t make sense for us to go back and recreate the society we read about

in Leviticus. But, neither can we ignore what has been. We have to live in

continuity with the history of God’s people.

In Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (in chapter 6) he

is writing to some in the church who heard that Paul taught that we are no

longer under the Law. They thought to themselves that they were free to do

anything they wanted. There was a catch-phrase they used- “All things are

lawful for me”. And Paul used it to correct them. He said,

“‘All things are lawful for me’, but not all things are beneficial. ‘All things are lawful for me’, but I will not be dominated by anything” (1 Cor 6:12).

They were improvising

the 5th act, but they were ignoring the first 4 acts. They weren’t

living in continuity with God’s story and God’s people. That doesn’t mean they

should be recreating an Old Testament community- they are in act 5, not act 2

or 3.

Paul goes on to say in this chapter that they should not use

their bodies for sexual immorality. That wouldn’t make sense in terms of the

story they are a part of. Paul says,

“do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, which you have from God, and that you are not your own? For you were bought with a price; therefore glorify God in your body. (1 Cor 6:19-20).

You

are a part of a bigger story so you need to act according to that story. It

doesn’t mean you have to repeat what has been. We are free from the Law, so

that’s not the phase of the story we are living in, but we are still God’s

people. As Jesus says in our Gospel reading,

“Those who love me will keep my word, and my Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them.” (John 14:23).

We have a Lord and our actions matter. As God’s

people we are a part of a community that stretched through the centuries and

our actions have to be considered in light of that community. As Christians

when it comes to ethics we should never really be asking “what can we get away

with?” Instead we should be asking, what is in keeping with my being salt and

light in this world? What is in keeping with me being a child of God and a

representative of Christ? How should I use the freedom Christ bought for me

with his blood? What is in keeping with being a temple of the Holy Spirit and a

member of the body of Christ?

Christian ethics aren’t always a black and white matter, so

it’s not always easy or clear. It takes prayer and a close relationship with

God and an intimate understanding of the Bible. But you aren’t alone in this.

We do this as a community under the direction of the Holy Spirit. Our ethics

are very relevant to the modern world, but we can’t just forget about the

community we are a part of and accept whatever ethics tend to be popular at the

time. Our ethics aren’t determined by television, they are determined by discerning

God’s direction as a community under the authority of the Bible empowered by

the Spirit.

[1]

The inquisition and the witch

trials are another historical incident that is often presented as an example of

the horror Christians are capable of. There was an estimated 30-60,000 people

that were killed under the witch trials of Western Europe. But, these were not

generally under the direction or approval of the church. According to the

theologian and historian David Bentley Hart, “the church’s various regional

inquisitions’… principal role in the

early modern witch hunts was to suppress them: to quiet mass hysteria through

the imposition of judicial process, to restrain the cruelty of secular courts,

and to secure dismissals in practically every case” (Atheist Delusions, 76). “It was the Catholic Church, of all the

institutions of the time, that came to treat accusations of witchcraft with the

most pronounced incredulity. Where secular courts and licentious mobs were

eager to consign the accused to the tender ministrations of the public

executioner, ecclesial inquisitions were prone to demand hard evidence and, in

its absence, to dismiss charges. Ultimately, in lands where the authority of

the church and its inquisitions were strong- especially during the high tide of

witch-hunting- convictions were extremely rare. … In many cases, it was those

who were most hostile to the power of the church to intervene in secular

affairs who were also most avid to see the power of the state express itself in

the merciless destruction of those most perfidious of dissidents, witches”

(80). The sociologist and historian Rodney Stark has said, “the first

significant objections to the reality of satanic witchcraft came from Spanish Inquisitors,

not from scientists” (For the Glory of God, 221). Hart argues that “violence

increased in proportion to the degree of sovereignty claimed by the state, and

that whenever the medieval church surrendered moral authority to secular power,

injustice and cruelty flourished” (86). Again, this isn’t to say that the

church is innocent. It especially does not say that Christians are innocent.

All I’m trying to say is that the historical reality of the Inquisitions and

the witch hunts are more complicated than the stereotype that is sometimes

thrown in our faces.

Comments

Post a Comment